What are the philosophical roots of Wokery?

Science over feelings. Reality over ideas. Ontology over epistemology.

I am not a philosopher or a particularly sophisticated social theorist, but I think that to understand our current ‘woke’ cultural dispensation, we have to look under the surface and beyond mere instances of what seems to be an increasingly fractious cultural moment in the history of Western civilisation (perhaps a form of hyper decadence).

Intersectionalism, transgenderism, decolonisation and so on all share a common philosophical foundation. Those critical of ‘wokery’ need to understand this basic fact, and by understanding it, can move beyond the endless groundhog days of the ‘culture wars’.

The key thing to understand is that most ‘woke’ identity politics theorists have a social constructivist epistemology. This means that they reject any notion of truth or objectivity as all meaning is ‘internal’ to human perception. As such, social constructivists argue that all human knowledge is ‘socially constructed’ from extant cultural raw materials and we cannot know anything outside of our cultural shared frames of reference. In this, they draw deeply on postmodernism and its off-shoots, including post-colonialism, queer theory, and post-Marxist critical theory.

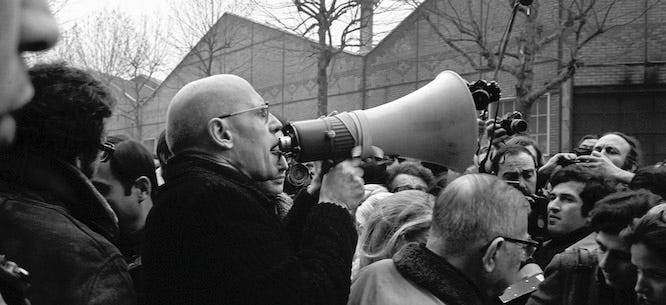

Foucault argued that all knowledge has implicit power relationships imbued within it. Knowledge is not ‘innocent’. Instead, it frames understandings in ways that have huge implications independent of the thing these understandings are attempting to describe. For example, as a gay man, Foucault was acutely aware of how the discourse on homosexuality had historically changed and he traced this through the ancient history of Greece to the present day; from its celebration to its medicalization to what is today a far more liberal perspective to the extent we now have a Pride month every year. The key insight is that though homosexuality has remained a constant across different historical cultures, the way it has been understood (socially constructed within cultural frames of reference) has changed. As those cultural discourses changed, so did the way society views gay people—hence the famous power/knowledge dyad within Foucault’s ideas.

Similarly, Derrida argued that Western philosophy, and by extension western culture, is composed of a series of hierarchically organised binaries such as man/woman, civilized/primitive, western/non-western and so on. One part of the dyad was seen as better and superior to the other.

Decolonial and post-colonial theorists took these ideas and argued that these discourses have permeated western civilization and have huge legacy effects on the present day. These theorists' political goal is to establish the radical contingency of knowledge and deconstruct dominant or ‘hegemonic’ ways of constructing knowledge. By doing this, the ‘Eurocentric’ self-belief and confidence of western civilization would be undermined, and by extension Western political hegemony. (p.19) Knowingly or otherwise, it is exactly these kinds of theoretical ideas that University bureaucrats are drawing from when expounding the need to decolonize their institutions.

More broadly, we can see the ways in which these theories have impacted Western culture and our current ‘culture wars’.

The social constructivist stress on self-actualization and definition through language places primacy on what is felt or perceived over what is real. Debates on gender self-identification, for example, explicitly call upon this social constructivism whereby gender, as a social construct takes precedence over what so-called gender critical feminists and scientists argue, are in fact the biological reality of sex differences.

Similarly, the advocacy for ‘indigenous’ knowledge or the castigation of white, Eurocentric curriculums is drawing upon a form of radical postmodern judgmental relativism. The collective sum of cultural wisdom and knowledge is thus transformed from the interplay of ideas towards an approximation of truth to one of multiple truths and power plays to impose dominance (the Foucaultian view). Similarly, this form of social constructivism and judgemental relativism transforms academics within Universities from fallible but authoritative arbiters of the sum of human knowledge to being part of a broader political struggle between the oppressed and the oppressors. If there is no truth, academic authority cannot exist and to claim as such is to impose power onto others. From this epistemological commitment flows much of what we see in the Anglophone West.

The importance of science and ontology

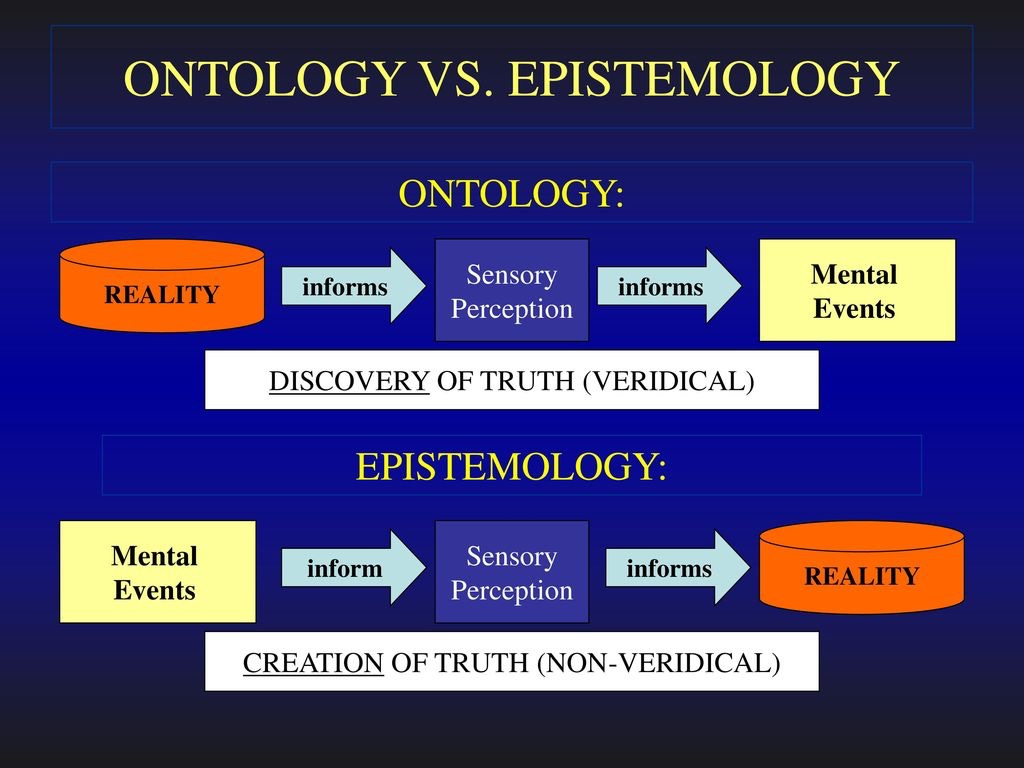

As outlined above, social constructivism is primarily concerned with questions of knowledge, how humans come to understand the world and the forms of power involved in those processes. In short, it places emphasis on epistemology or how we know what we know.

In contrast to this approach, I would like to flag up the value of scientific realism, which argues for the primacy of ontology. This is the notion that being or reality is “ontologically prior to knowing and, therefore, understanding the nature of an object of research – ontology- precedes a consideration of how the researcher is going to get to know it (more deeply) – epistemology”. This emphasis on ontology is important.

First, as Sayer has argued, the postmodernist form of judgemental relativism “appears to have the virtue of being egalitarian and open-minded” but this elides the normative belief that “because everyone is or should be regarded as equal, the epistemological status of their beliefs must also be equal”. In short, it takes the laudable moral goal of human equality and applies it to the status of different beliefs where all exist in a form of judgement-free horizontalism.

Second, the driving dialectic that should be at the heart of our institutions of learning, that of unfolding human knowledge that moves humanity towards higher levels of understanding, is being abandoned. Instead, the organising principle becomes one of radical deconstruction driven by a desire to compensate for the legacy effects of the alleged perfidiousness of western civilisation and a form of technocratic therapeutic reform to protect the self-esteem of those posited as victims. The assertion that all human knowledge is equally true, and by extension, a mere power play, makes it easier to understand this abandonment of basic and fundamental academic principles. Aside from the obvious fact that if all knowledge is relative, why should we subscribe to the assertions of the woke critique itself, this form of unbounded judgemental relativism abandons any notion of reality or truth for a seeming endless play on meaning and identity.

In contrast, scientific realism posits the mind independence of the world. Indeed, this is what makes it a realist theory: it posits the existence of a reality that is ‘out there’. Given the world has properties that exist independently of human knowledge and remain ‘true’ independently of what we may believe about these things, the models we adopt to explain that reality is bounded as well. For example, we can believe in the capacity of human beings to fly by flapping their arms, but the mind-independent reality of gravity means that no matter how hard we may flap, or believe in human flight, those beliefs can never be true.

Importantly, this claim for mind independence or ontological realism is not an assertion that the objective world presents itself to us in an unmediated form. This is a form of naïve realism. Rather, given the mind independence of the world, it is possible to build conceptual models and make plausible judgements about their truth. That is “ontological realism and epistemological relativism are conditions for rational truth-judgements. On the one hand, without independent reality, truth-claims would be meaningless. Truth-claims have to be about something”.

It is this realist mind independence of the world that sets boundaries on our contingent theories of it (or why humans cannot fly). It also operationalises a form of judgemental rationalism that then adjudicates between different truth claims. As such, the worth and value of a specific understanding of the world is not decided by the identity of the progenitor of those ideas, but by their rational veracity in describing the phenomenon to which they are directed.

As such, this epistemological relativism (as distinct from the postmodernist judgemental relativism) argues that all human knowledge is in fact relative, fallible and context-dependent but is nonetheless bounded by reality. Perhaps this is why the sub-title of Kathleen Stock’s book was “Why reality matters for Feminism”?

In short, many of the often fraught debates being had in the culture wars are based on a deeper philosophical foundation that I believe emerges from the French postmodernists, that has then spread through various other forms of “post”-scholarship: post-marxism, post-colonialism, post-structuralism and so on. Given the huge turnover of social science and humanities graduates and the hegemony of social constructivism within these disciplines, it is hardly surprising that these ideas now form the common worldview of much of the cultural elite of the Anglophone West, and feed into seemingly endless ‘culture wars’.

Interesting article in Scientific American this month by a 'systems neuroscientist' on the difference between 'outside-in' concepts of perception and 'inside-out' ones. Essentially, it's about the extent to which the brain prepares models of how to interpret the signals it is receiving through eyes, ears etc. , as opposed to simply receiving inputs and inexplicably creating meaning to attach to them.

He has changed his views of this , after having taught outside-in theory for decades and realising it has always glossed over its dependence on an observer to generate meaning. Now he favours inside-out, in which thd brain develops and accumulates, over time, a body of information about the perceived object which enables it to attch meaning to it.

"the interplay of ideas towards an approximation of truth to one of multiple truths and power plays to impose dominance (the Foucaultian view)."

It is this relationship between "power plays" and "dominance" that interests me. What is "power" in "power plays"? What is meant by "dominance"? Are we talking about a correspondence theory of truth in relation to "multiples truths"?